The Yang Slinger: Vol: LXII

To work in sports media is to cover Black athletes and coaches. But are we (white journalists) being fair? Are we being empathetic? Are we being righteous? And do we ask the right questions?

I have never particularly cared for Deion Sanders.

It’s not that he’s loud (though he is).

It’s not that he’s brash (though he is).

It’s not that he was a semi-asshole after my 1990s Dallas Cowboys book, “Boys Will Be Boys,” hit shelves back in 2008 (though he did go on Michael Irvin’s radio show and sorta slam me).1

No, I have never particularly cared for Deion Sanders because—in large part—I see him as a flimflam artist; as a guy who talks a big game, convinces people he’s all about their improvement—and then either A) Bolts for a better/cooler/more prestigious opportunity or B) Ruins everything around him.

If you don’t trust me, take a few moments and research Prime Prep Academy, the school Sanders helped launch 11 years ago. Or look at his departure from Jackson State, when he went from swearing, “I am SWAC!” to strip mining the program of assistant coaches, star players and—as you’ll see play out these next few years in Jackson—hope for a prosperous future.

I see a lot of Don King and Donald Trump in Deion Sanders—the boasts, the brags, the us (team) v them (media) bellowing, the playing to large crowds. I think Deion has a pretty shitty/extensive history of convincing young Black men he’s looking out for them, when in fact he’s looking out for him.

Again, I have never particularly cared for Deion Sanders.

Which leads me to this past week.

In the aftermath of Saturday’s shocking 45-42 win by the Sanders-coached Colorado Buffaloes over TCU, I took to Xitter to express my displease over a moment from Sanders’ post-game presser in the home stadium’s interview room. It happened when Ed Werder, the longtime ESPN football guru (and a highly respected vet), asked Sanders some innocuous question, and was hit with this …

This irritated the fuck out of me.

First, why is OK to speak to someone (especially a guy with a history) like that? But second—I didn’t realize we, in the media, are supposed to root and cheer and “believe” in a team. I didn’t realize if we predict a loss we’ve somehow done a program wrong. I didn’t realize someone (understandably) thinking Colorado would struggle this season warrants a flogging. I thought Sanders was full of shit, and I (fuckity fuck) Tweeted about it ,,,

Then there was backlash.

And more backlash.

And a really strange Sports Illustrated article from a reporter who never bothered to call me.

And then I stopped to think about stuff.

To really think about stuff.

Being a white guy in sports media is easy.

We are—by far—the majority. We’ve created the rules, the playbooks, the approaches. Wanna know how much time a reporter can spend inside a Major League clubhouse? Ask a white guy—he came up with the duration. Wanna know something about the 1982 NFL season? Ask a white guy—they created every single media guide. To be a white guy in media is to rarely fear for your job2. It’s to never have your credentials questioned. Being a white guy in sports media is like being a member of the Busch family in beer. It’s like being a senator’s son with an application to Princeton. You are, with rare exceptions, not merely safe, but secure and granted a lifetime of puppies and strawberry milkshakes.

But being a white guy in sports media also comes with blind spots—ones, I suspect, the vast majority of us are cursed to possess. I wanna explain this well, and it’s not all that easy: [clears throat] To grow up white in America is not to grow up Black in America. And while that sounds obvious, it’s the intricacies that matter. Like, when I was a kid being raised in Mahopac, N.Y., I attended a school with, oh, 1,500 students. Of those 1,500, maybe six were Black (I only remember four). Which means I was exposed and indoctrinated into to every ignorant hick-town cliche and presumption one could muster about Blacks—lazy, naturally athletic, not too smart, whiney, entitled. I actually remember, as a little boy, seeing a Black classmate with sticky hands (he was probably using glue or something) and thinking, “Oh, that must be a thing Black have.” I also remember multiple classmates agreeing that there were “two types of Blacks—the good ones of the n——-s.” Then, someone turning to my closest friend (one of the two Black kids in my grade) and saying, “Don’t worry. You’re a good one.”

And while age and exposure change a person, the real task is changing not merely your acceptance of folks, but your willingness to understand, empathize, recognize that while others may well handle a situation differently, it doesn’t make it incorrect or offensive. With sports journalism, that’s particularly daunting because not only did most of us rise out of towns like Mahopac, but we’ve seen the same acts and actions not merely repeat themselves across decades, but embed into our brains. I mean, think about it. Is there that great of a difference in the behaviors of Bear Bryant and John Robinson than the behaviors of Nick Saban and Lincoln Riley? When George Brett—white third baseman—did his thing for the Kansas City Royals, we hailed his grits and guts. Just as we did with David Wright when he played third for the Mets three decades later. We, the largely white media, saw the grits and guts. We loved it. Understandably—because (in a strange and creepy way) it reinforced everything we’ve been taught about the white athletic success saga. Whites work hard. Whites bust tail. Whites have to grind in ways Black do not. Whites don’t talk shit. Whites don’t boast.3

But, far too often, we fail to grasp our limited visions. We know what we know, and what we know is the “proper” way to behave. You show humility. You show grit. You show hustle. You …

Don’t act like Deion Sanders.

You just don’t.

And this, dear readers, is what I’ve been asking myself: Do I object to Deion Sanders solely because I don’t like his behaviors, or do I object to Deion Sanders because he’s a loud, proud, brash Black man—and I’m simply not used to that type of character? Could it be that, despite covering Black athletes and coaches and administrators for decades, I still have a bit of Mahopac in me? A bit of vision bias? A bit of lazy, cliched behavioral expectations? We loved Barry Sanders (acceptable Black man) because he scored touchdowns and flipped the ball to the official. What dignity. We hated Deion Sanders (unacceptable Black man) because he scored touchdowns and danced. What arrogance.

“Verbally confident Black people in all walks of life rub some white people the wrong way, and sports puts that dynamic in a bigger than normal spotlight,” Ty Rushing, a Black political writer for Iowa Starting line, told me. “I think one of the biggest things is we need more POC in those spaces who can relate with the subjects they cover on a personal level and white reporters should be more open-minded and willing to really listen and learn about the experiences the athletes they cover go through.”

I reached out to a good number of media friends for this entry, most of whom are Black and involved in sports. And the most-repeated take was (more or less): To really, really, really cover Black figures correctly (as a white person), you have to dig deeper than deeper than deep. You have to toss away any normalized expectations of “proper” behavior via the embedded white code America often runs by. You have to ask yourself, Who is this person? What has this person seen? What has this person experienced? What does this person carry with them—because they’ve grown up Black in the United States?

As an example, I’m working on a Tupac biography, and I’ve been spending a large chunk of time in low-income Black neighborhoods. And when I interview those who knew (and oftentimes loved) Pac, what I keep hearing is this: None of us expected to live past the age of 25.

Now, think about that: “None of us expected to live past the age of 25.” How many white people walk the earth with that perspective? How many whites worry about reaching 28? Reaching 30? Perhaps the whitest life-expectation scene in movie history dates back to 1997, when Jack Dawson tells Rose DeWitt Bukater that she’s gonna wind up an old lady with lots of babies. They’re literally grasping onto a plank of wood in the icy Atlantic, and Jack knows Rose will reach old age. He’s certain of it. Because why wouldn’t she? She’ll get home, find a pad, meet some wealthy white dude, move to the suburbs and enjoy her lawn and espressos.

To walk the earth as a Person of Color is to carry the awareness that shit is stacked against you. And that’s something I have—quite literally—never felt.

“It does start with introspection and exploring who do you give the benefit of the doubt to, when and why they get the benefit of the doubt—and truly understanding/noticing what is at the root of you being irked, why and how that impacts your perspective,” said Angela Taylor, the Black former general manager of the WNBA’s Washington Mystics and a women’s basketball analyst. “Using boring white coaches as a standard is a choice society has made and it doesn't account for the fact they have the privilege of not having to represent an entire identity group. Does more diverse representation shift the weight we attribute to one's choice for how he used his platform? Deion's antics aren't for everyone, but does consensus determine what is right and what is wrong.?”

In regards to Deion, Evan F. Moore—Black longtime sports writer and author—said the question isn’t whether Sanders’ tactics are (or are not) digestible, but, well, why do we (the white media) go out of our way to call him out (“when white coaches at blue blood programs have done similar things,” said Moore). And it’s a helluva point. Is Nick Saban not doing the same shit? Is Dabo Swinney not doing the same shit? Fuck, how about Lane Kiffin, the Ole Miss head coach who exercises the ethical compass of a Visa Gold inside Thee DollHouse. Kiffin has yet to meet a potential recruit he hasn’t buttered up, has yet to find a program he treats with any semblance of loyalty. Yet while Kiffin is hailed as the guy who has resurrected Ole Miss (after slinking away from Florida Atlantic), Sanders will always be—to many of us—the snake-oil salesman who ditched Jackson State. “I’ve been fascinated at the white coaches who’ve publicly criticized him for following the rules,” said Roy S. Johnson, the veteran Black journalist and author. “That’s laughable.”

“Overall, mainstream media still has issues with how they cover Black folks specifically—let’s be honest, in the major sports that’s who you’re talking about—because they still use coded language to describe our failures and successes,” said Jemele Hill, the longtime (Black) scribe and author. “I couldn’t help but notice some of the conversation around Colorado’s win. Some people were expressing surprise that his team was actually disciplined and offensively cohesive. As if they were going to come out playing like the Texas State Fighting Armadillos from ‘Necessary Roughness.’ It’s also worth noting that Sanders skipped steps to become a head coach and that’s typically a privilege afforded to white coaches, who almost always given the benefit of the doubt. Sanders wasn’t and that showed up in a lot of the coverage.”

So what to do?

First, we need to continue to diversify journalistic entities, so the people reporting on stories understand the plights of those in the stories.

But second, we, the white journalists of America, need to take a step back. “We have to consider our biases—that’s basic,” said Jonathan Eig, the white author of King: A Life. “As a reporter, your job is to report what you don’t know. So if you have particular blind spots, you have to work harder to learn what you don’t know.” In other words, the next time we describe a Latino infielder as lazy and lackadaisical, we need to think about his downtrodden Dominican hometown, where his dad worked for peanuts to take care of his three kids. We need to think about his journey to America at age 17; of not speaking the language but landing in Single A Lake Elsinore and living in the spare bedroom of Mike and Marci Gault—who bring him to church every Sunday morning (even though he’s not religious) and insist he speak English and eat Marci’s homemade pepper-and-cucumber pizza.

We need to think about the Black kid from Gary, Indiana who never before wrote a check, now making big bucks in Los Angeles and living it up. When we criticize him for buying a Mercedes with all the trimmings, we need to ask ourselves, “What has he experienced? What does he know?”

And when we see a coach walking confidently and talking the talk, we need to question whether we’re bothered because it’s bothersome (Phil Taylor, Black former Sports Illustrated writer: “Part of Deion's act irks me, too. Probably because it's not my style. The cockiness, the ‘keeping of receipts’ as though questioning anything about him or his team is some kind of personal insult—no question he goes overboard sometimes.”) or whether we’re bothered because it’s not what makes us comfortable and fails to travel along the familiar, well-worn path that we’ve always navigated.

“When Deion asked, ‘Do you believe now?’ in that presser I think he had two purposes,” said Taylor. “One was to embarrass the reporter for not having been on the Deion bandwagon. That was cocky, asshole Deion. But the other purpose was to say ‘Do you believe now’ that I'm not just a mouthy Black man, that I'm a skilled coach who knows what he's doing? Do you believe now that I can build a program that can beat schools who never would have dreamed of hiring a guy like me? Black people in all walks of life are still, in 2023, battling the perception that they aren't truly qualified even when they are successful at their jobs. I think that's why I would venture to say Black football fans are a lot less bothered by Deion's occasional arrogance than some white media members are.”

I cannot disagree.

The Quaz Five with … Jim Aberdale

Jim Aberdale is a supervising producer for NBC Sports Boston. He’s been doing the gig for quite a while. You can follow him on Xitter here.

1. Jim, you're a supervising producer, for NBC Sports Boston. I feel like that's a title we all know, but a job we're all unfamiliar with. So ... what do you do?: I’m part of our network’s Celtics group—we have a dedicated group of hard-working and knowledgeable professionals who work on all things Boston Celtics basketball throughout the year. As you’d expect, our busiest time is October through May/June. During the season, I primarily produce our Celtics studio shows—these are our pregame, halftime and postgame broadcasts. We do studio shows approximately 110 nights per year (82 regular season, 4-to-5 preseason, and anywhere from 15-to-25 postseason games). I also produce a small handful of our Celtics game broadcasts each season. I’ll produce some of our specialty programming too—I worked with a small group to create, “The ’86 Celtics” and “Anything Is Possible: The Story of the 2008 Celtics.” A couple of years ago, in honor of the Celtics’ 75th season, I led a project where we revisited the Top 75 moments in franchise history. Another one I enjoyed was a project called “The Last 20,” where I sat down with the Celtics’ co-owners and we looked back at all the twists and turns during their two-decade tenure, then turned that conversation into several short-form segments that ran in the pregame show throughout the season.

As for what a supervising producer actually does, it varies depending on if I’m working on the fast-paced day-of-game programming or if I’m involved in a longer form project. For day-of-game, it’s all about the details, both big and small. You’re constantly consuming everything about the team, the opponent, and the league. From there, you’re trying to figure out how to align what’s happening in the Celtics/NBA news cycle and how to put our on-air talent in the best position to analyze all this information and present it to the viewers in an informative but fun way. Collaborating with others is essential—I’ll work with producers, associate producers, production assistants, directors, editors, sales, marketing and management throughout the day. Story selection, rundown building, approving graphics, and approving edits are a huge part of the job. You’re leading up to the live broadcast, so you’re constantly up against the clock to make sure everything is done for showtime. Executing a live broadcast is the most exhilarating part of the day—you’ve got one chance to get it right when it comes to live television.

For longer form, you have more of a chance to breath and give things a bit more thought. As a starting point, there’s a substantial amount of research that has to be done. From there, it’s crafting the story you want to tell followed by tracking down interview subjects, lining up shoot locations, and executing interviews with your camera crew. After that, it’s all about cutting down the interviews into small usable soundbites and weaving the story together through use of video, still pictures, and narration.

I’ve truly come to enjoy long-form storytelling in recent years, even beyond my work at NBC. I find myself aspiring to collaborate with content creators of all kinds in a freelance capacity, whether that’s for television/film documentaries, or books. My favorite parts of the process are interviewing, storyboarding, writing, researching and copy editing.

2. You've held you job for 23 years. How, in this age of rapid-fire turnover, is that possible?: I think it’s a combination of several factors. First, I’m passionate about what I’m doing. I watched our network when I was a kid growing up in Western Massachusetts (SportsChannel New England was the brand in the 1980s and 1990s) and back then, I enjoyed watching Mike Gorman and Tommy Heinsohn call the games. I never imagined actually being a part of it. Second, we have a ton of talented people working at the network, which in turn makes this one of the strongest regional sports network in the country. Third, Boston is the best place in the country to watch and observe pro sports (at least in my mind). There’s such a massive appetite for sports talk/sports coverage in this market, due in large part to the staggering success of the pro teams over the last couple of decades. I think that helps when it comes to needing good people to put the content together for the public to consume. Lastly, there’s a healthy dose of good ‘ole fashioned luck involved—I’m simply extremely lucky to have gotten to do this for as long as I have. I say to people all the time, I’m just as invested in making quality sports television today as I was the day I started back in July of 2000.

3. What's your craziest experience dealing with an athlete or coach during your career?: From 2003 through 2011, I was our network’s Red Sox field producer, so I was around some colorful and wildly successful Red Sox teams from spring training through October and was fortunate enough to see history unfold right before my eyes on multiple occasions. In 2008, Jonathan Papelbon’s mom had passed along some video of him in high school where he and a buddy reenact a scene from Dirty Dancing (Papelbon was Patrick Swayze, his friend was Jennifer Grey). We made secret plans with David Ortiz to call a fake team meeting to show the video to the team on the monitors in the clubhouse. Ortiz gets into the middle of the room, tells everybody he’s got something he wants them to see, then hits play on the TV. Our cameras were rolling on the team’s reaction. The entire team was howling so we felt like we had struck gold. Terry Francona, the team’s manager, was not amused. He called our cameraman (a leader on the hijinks) and me into his office. He didn’t yell and scream, but it was clear he was not pleased. He explained next time we should have at least given him a heads up. We’re lucky that result wasn’t more intense than that.

Runner-up story: Not an athlete or coach, this falls into the “craziest-experience-dealing-with-an-object” category. So the Red Sox break the curse in 2004, our crew catches a flight back from St. Louis and decide we absolutely need a player guest on our set the next night. I reached out to Bronson Arroyo; he agreed to drive to our studios north of Boston. On a whim, I contacted Red Sox media relations and asked if they could somehow bring the World Series trophy to display on the set alongside Arroyo and our hosts. They were an extremely helpful group and agreed—someone in the department would drive it up. After the show, for whatever reason, it turned out the trophy had taken a one-way trip to our studios and the media relations assistant charged with making sure it made its way back to Fenway needed a ride back to the ballpark. Lo and behold, the media relations assistant and I carefully lean trophy in the back seat of my black Chevy Cavalier and throw the seatbelt around it. Off we go into Friday afternoon rush hour traffic. We eventually make our way onto the Massachusetts Turnpike and come upon a toll booth. Back then, there was a real-live person collecting tolls in the booth. We rolled on through, and I can still see the look on the toll collector’s face as he peered into the back of the car and caught a glimpse of the World Series trophy that had been won by the 86-year curse-busting Red Sox in St. Louis around 24 hours earlier. It looked like his eyes were going to burst out of his head wondering how the hell the trophy ended up in the back seat of a beat up Chevy. Wish I could go back and find him and interview him about what he was thinking in that moment.

4. Boston fans have a rep. Some good (passion). Some bad (sorta racist). What can you tell us?: I find most Boston sports fans (not all, but most) to be intelligent and engaging and oftentimes humorous when it comes to watching, discussing and debating sports. As for the bad you mentioned, I have certainly read various stories from over the years but have not witnessed anything in my time at Fenway, Gillette, TD Garden or elsewhere around town.

5. Can you still get up for sports? All these years, all these plays, etc. What does it for you, if anything?: It’s certainly different than when I was growing up as a fan. Back then, I was beyond hyped for every single game I watched or attended. Things started to turn for me as far back as 2003, when I first starting covering baseball in person. It was pretty jarring to see how different things were in real life compared with how you imagine them to be. I do still “get up” for sports but I’m honestly more interested in our coverage being the best it can be, that’s what truly motivates me and has for at least the last 20 years. I do have an interest in the Celtics playing well, as a better team means more viewers (fans simply watch more often and longer when their team is winning). And yes, there is a still a degree of “fandom” residing inside me when it comes to the Celtics.

Bonus (rank in order—favorite to least): black and white cookies, Thailand, Haley's Comet, Mitt Romney, Mac Jones, Jake Paul, Sidney Poitier, Philadelphia cream cheese, onion soup: Thailand, Haley’s Comet, Sidney Poitier, black and white cookies, Philadelphia cream cheese, Mitt Romney, Mac Jones, onion soup, Jake Paul.

Ask Jeff Pearlman a fucking question(s)

Here’s a wacky idea—ask me any journalism question you like, and I’ll try and answer honestly and with the heart-of-a-champion power one can expect from a mediocre substack.

Hit me up in my Twitter DMs, or via e-mail at pearlmanj22@gmail.com or just use the comments section here …

From Fritz: Reading about Bo Jackson's cancellation efforts got me wondering—which book of yours would you say the subjects were on aggregate happiest/most content with? I don't mean this in a snarky way at all, I've all read all of your sports bios. But I was just curious if there was a yin to to Bo Jackson's yang in terms of subjects' reaction to your books?: Hmm, that’s a helluva question. So Bo wasn’t happy, and I’m sure Brett Favre probably wasn’t thrilled. I never heard from Barry Bonds, and I’m guessing he never read the book. Roger Clemens Tweeted angrily about me, but he’s functionally illiterate and almost certainly didn’t check any pages. I heard very lovely things from Jeanie Buss, Lakers owner, about both “Showtime” and “Three Ring Circus.” So that made me pretty happy.

A random old article worth revisiting …

This is from the Sept. 18, 1977 Tampa Tribune. I was actually seeking an article about the Buccaneers’ first-ever game, but one can never, ever, ever bypass a chance to pay homage to Greg Luzinski …

This week’s college writer you should follow on Linkedin …

Emilia Cuevas Diaz, Chapman University.

The opinions editor for The Panther, Diaz penned an absolutely gorgeous piece, headlined, I USED TO DANCE IN THE RAIN.

Wrote Diaz …

I used to dance in the rain when I was little.

I remember one time when my brother and I were in my house with our parents, and it started pouring rain. My mom was usually very strict about not letting us out in the rain unless it was absolutely necessary, and then only if we were properly equipped with rain jackets, boots and umbrellas. Except this time, we managed to convince her to let us go out in the rain and have fun for a few minutes.

It was glorious.

It was so exciting to be just standing in the rain. The drops falling on our faces, the wind in our hair, my brother and I laughing and spinning around just because we could… After that, every time it rained, I wanted to go outside and have fun. So I did.

I used to dance in the rain. When it started raining in the middle of basketball practice, I twirled around the court. When the rain caught me in the middle of walking my dog, I started laughing. When I was doing homework and I heard the tell-tale tip-tap of rain, I rushed out to the garden. I used to dance in the rain. But not anymore.

At some point, practicality got in the way. I don’t think of dancing anymore when it rains. If I’m outside, I think of how I’m going to have to wash my clothes because they’re wet. If I’m at home, I think of how inconvenient the rain is for me to get anything done outside. If I’m at school, I find it annoying because it means I have to stay inside a building or go to class drenched. Rain transformed from a source of joy to an evil to be dealt with.

It makes sense when I think about it. Back then, I didn’t have to deal with any of the consequences. I was just a kid dancing in the rain. Now, I’m (technically) an adult.

I loved every word.

One can followed Emilia on Linkedin here.

Bravo.

Journalism musings for the week …

Musing 1: So thrilled to read this Poynter piece—HOW ONE REPORTER COVERS THE US OPEN FOR NEWSPAPER ALL OVER THE COUNTRY—from Pete Croatto about the hardest-working dude in tennis media—Michael J. Lewis. There are plenty of under-appreciated scribes walking the earth—hard-working, for-the-love-of-the-game scrappers, and Lew symbolizes that. Plus, he’s always been a top-shelf pen wielder.

Musing 2: There’s a guy named DJ Blessone who goes by IsmokeHiphop, and runs a popular YouTube feed to offers takes on sports, music, pop culture, etc. And after the Deion Sanders flap, he took to his channel to slam me for all sorts of stuff. I watched it, objected and politely e-mailed Blessone my complaints. He responded with one of the kindest messages I’ve received in many moons, as well as the following video. Honestly, the class and decency warmed by soul.

Musing 3: Seth Davis is my longtime friend and former Sports Illustrated colleague, and he recently left The Athletic to work for The Messenger. In many ways, Seth paved the path for The Athletic college hoops coverage. He was one of the site’s first writers, first big names, first people whose presence screamed, “Holy shit! These guys mean business!” It’s a huge loss for the struggling sports site.

Musing 4: I don’t know her, name, but there’s a woman who keeps trolling future inmate Peter Navarro every single time he asks for money on a street corner. And I would like to marry here ASAP.

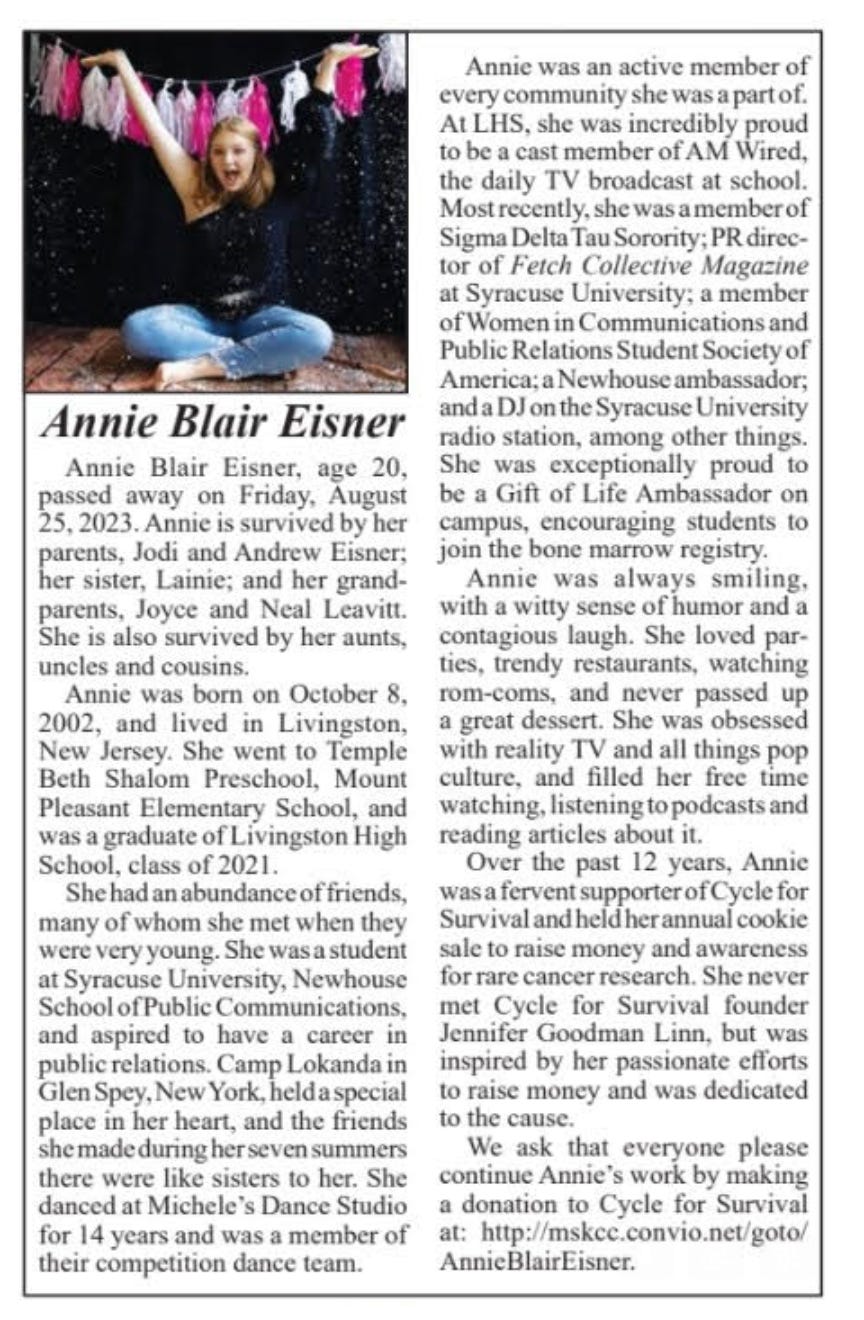

Musing 5: One of my dear friends is a journalist, Adrienne Lewin, who told me about a local 20-year-old New Jersey woman who died recently. I wound up reading all about the remarkable Annie Blair Eisner, and I hope that you do, too. RIP.

Musing 6: I don’t have any real problems with legit investigations into Hunter Biden. He’s clearly a troubled dude who has done some, eh, less-than-kosher shit. But if we’re going after Hunter, we damn well better save some bullets for Jared Kushner, who continues to cash in on four years of White House chillin’. This piece, from Axios’ Dan Primack, breaks it down.

Musing 7: Something genuinely endearing in an online sex worker trying to raise money so her mother can open an independent book store and candle shop. Warmed my heart.

Musing 8: New Two Writers Slinging Yang stars Stephen Marche—essayist, former Esquire columnist and author of, "On Writing and Failure."

Quote of the week …

OK, maybe it is—a little.

Admittedly, this has changed with the off-a-cliff media landscape. But y’all get the idea.

Even writing that shit makes me cringe.

Perspective is something with which we probably all struggle. Empathy is something else that feels like it’s in very short supply. I’ll share these couple of unrelated-related thoughts that popped into my head while reading the Deion part of the article ...

And ... first ... in the interest of full disclosure ... I’m a middle aged white guy from northern NH who grew up in teeny-est tiny-est more diverse southern NH. And I’m a lapsed Catholic. I offer that for ... perspective.

Thought number one: More than a few years back when I still killed some time on Twitter ... usually reading ... occasionally replying ... and rarely posting ... I came across a post from a somewhat prominent woman who is Jewish who said the phrase “... it’s all about the Benjamins” was antisemitic. I was aghast. I used that phrase whenever I was talking cynically about the power of money and corruption and ... of course ... I was always always always ALWAYS picturing giant banded stacks of banded $100 bills. So, no way. Not. Antisemitic.

And then I thought about it. Was it possible, I asked myself ... that this woman might have a slightly different perspective on the matter. Well ... it only took about two minutes with Mr. Google and a couple of genuinely horrific rabbit holes to understand my mental image of the phrase and the origins of the phrase were two entirely different things ... and other than to type the words just now ... I wiped the phrase from my verbal quiver. I can still be cynical about money and corruption ... but I need not, even if unintentionally, help to perpetuate such a terrible thing. Life lesson for Timmy: Listen to those who know.

Thought number two: My mother-in-law did not like me. At all. Ever. Many of the folks who knew her, grew up with her, were friends with her, loved her ... to a person ... assured me it had nothing to do with me ... she’d been in a couple of bad relationships and did not trust men. Period. End of story. “Don’t,” they assured me, “take it personally.” I took it personally.

My wife and I worked (and still work) double-extra hard to separate in-law nonsense from us. Most days we succeed. But I’m not gonna lie ... sometimes the relentless dislike and loathing was a grind. Sometimes it encroached on marital bliss. Sometimes it created stresses and pressures that didn’t need to exist (because, once again in the interest of perspective and full disclosure ... I am a delightful fellow). They existed. And they existed for one reason only ... I was a man. Gotta tell ya ... that felt entirely wrong and unfair.

Then one day I thought ... that’s ONE mother-in-law. One person. One person treating me unfairly for no other reason than my state of ... being. And I wondered ... how must it be to have not just one relative treating me that way ... but an entire system looking askance at me ... for no other reason than ... being. To equate one angry in-law (who, of course, had her own story, her own traumas, her own reasons) ... with the injustices of systematic racism is almost so laughable as to make me almost hesitate to share the thought ... because one is definitely not the other. Yet, the one led me to feel terrible on so many occasions ... that in drawing the analogy in my mind left me realizing I was incapable of truly being able to fathom, as a middle aged white guy, the weight of the racism that is baked into our culture.

Thanks for the interesting thoughts, Jeff. Part of me thinks that color has nothing to do with it--that a pompous a-hole is a pompous a-hole--but now I'm wondering as a white man if we should just sit and listen more instead of saying anything at all.