The Yang Slinger: Vol. XIII

Are Covid restrictions a temporary pain in the ass—or the new (dreadful) normal for sports writers? Also, five questions with Doug Russell and the rocker's talent that was no illusion.

In the third quarter of last Sunday’s game between the Buccaneers and Jets at MetLife Stadium, Tampa Bay wide receiver Antonio Brown lost his mind.

With his team trailing by double digits, Brown—standing along the sideline—removed his pads and tossed some of his equipment to nearby fans. He then stripped off his black shirt and white gloves, chucked those into the crowd, ran across the field (while the game was being played) and into the end zone, egged on spectators with a funkadelic wave/jumping jack hybrid, flashed the peace sign with his left hand and jogged off into the darkened tunnel and what is most likely1 permanent NFL unemployment.

You’ve almost certainly seen it by now. It was b-o-n-k-e-r-s.

And in a normal pre-Covid world, where sports scribes cover games, then afterward enter the locker room to speak with players and coaches, we’d know so much more about what went down. Two of the NFL’s elite beat writers, Rick Stroud of the Tampa Bay Times and Greg Auman of The Athletic, chronicle the Bucs, and the myriad lessons learned through decades of sports coverage tend to commingle at such moments.

Or, put different: Were there no global pandemic to speak of, Stroud and Auman would absolutely own the story.

First, they would have entered the locker room.

Second, they would have taken stock.

Third, they would have attacked.

“I talk to everyone I can,” said Auman. “Not in a scrum, not in a Zoom where everyone hears what they say. You want to get insights on and off the record. What was said, who was wrong.”

“I’ve been told Brown felt things had changed when he returned from his [three-game suspension for faking a vaccination card],” added Stroud. “I want to know what changes Brown’s teammates witnessed. What did he complain about? Was it his rehab? The fact he failed to practice? Did he share any personal problems with them? The answers are in that locker room. You have to be in that arena to get them. You don’t always strike gold. But you have to at least try to dig for it.”

Back during my baseball-writing days at Sports Illustrated, I had a fair share of evenings roaming post-game clubhouses on deadline. And the experience is a merging of horror show and kinetic bliss—horror show because you’re simultaneously entering the same space as your competitors; bliss because it’s electrifying. And what I loved (and still love) is hitting up the little guys for big details. I first realized this was the way to go by watching Tom Verducci, the SI gangsta, work the room. As others headed toward Jorge Posada and Roger Clemens, Tom was in a far-off corner with Homer Bush and Ricky Ledée, peeling off small details the herd all missed. That’s how you report your way through a tornado—while the hacks and wanna-be Stephen A. Smiths travel the path of least resistance, you put all those years of experience to good use. You dig.

“We still haven’t heard the real story [of Brown],” said Stroud. “It’s a relationship business. You build trust with access. You gain contextual perspectives. What did the security guards see when Brown stormed off the field? Did he ask a nearby police officer assigned to the locker room to drive him somewhere? What was his demeanor when he entered the tunnel? Those folks may have some insight.”

Alas …

“We’re never talking to them from the press box on Zoom.”

This, sadly, is the reality of 2022, where Covid has rendered locker rooms off limits. Hence, instead of entering the Buccaneer quarters, Auman and Stroud (and every other reporter covering the game) were forced to sit by their laptops and watch just two men—coach Bruce Arians and quarterback Tom Brady—hold flat soda press conferences via Zoom.

Arians refused to discuss …

Brady was (yawn) Brady …

And that, pathetically, was that.

No follow-ups. No corner chats with fringe players. No angry teammates waiting to go off.

No … nothing.

The Buccaneer organization didn’t want the issue discussed at any great length, so they (as a collective) stopped discussing it.

Click.

“Talking to witnesses changes everything,” said Auman. “[Wide receiver] Mike Evans is the perfect guy to talk to. But [we had] no luck.”

The end result: Workmanlike-but-limited pieces from both scribes, a whole lot of social media guessing … and no real answer to the question: What the fuck happened to Antonio Brown?

This, sadly, is the likely future of sports writing.

The sky is falling.

It’s been falling for decades—and any unawareness to this dreaded reality can be chalked up to either not being a veteran writer or living inside a plastic bubble alongside kittens, strawberry ice cream cones and the fifth Backstreet Boy2.

In the years since I began my journalism career in 1994, access for sports writers has been steadily chipped away by owners who don’t trust/like the press, general managers who don’t trust/like the press and players and coaches who (wait for it) don’t trust/like the press. You can see it in every new and/or renovated Major League stadium, where clubhouses (once ideal meeting places for jocks and journalists) now feature 800 spots for ballplayers to hide. You can see it in the militaristic NFL, where not all that long ago writers roamed training camp fields and facilities with all-access passes and open invitations to lunch with Randy White and Ed Jones. You can certainly see it in the NBA, a league that over the past decade has cracked down on media access like no other.

Wait—hold that thought.

A quick story.

Back in 2013, when I was reporting my book about the 1980s Lakers, the franchise’s PR guy was named John Black. And through it all, John was fabulous. He helped me, pointed me in the right direction, gave me access. Best of all, he made it clear there were no expectations of kissing the organization’s ass. “Just be fair,” Black told me. “That’s all we expect.”

A few years ago, I researched and wrote another Lakers book—this one concerning the Shaq-Kobe years. By now Black had been (mercilessly, cruelly, callously, dickishly, unceremoniously) given the boot and replaced by his … um … eh … what’s the word … utterly useless fill-in, who could not have been less helpful. At one point, after a practice, I sat down with Mark Madsen, ex-Laker player/current3 Laker assistant coach. We were chatting away, having a wonderful conversation, when I spotted the publicist standing behind Madsen, giving me the hand signal to wrap things up.

After 15 minutes.

When practice was long over.

With Mark Madsen.

Who averaged 2.6 points per game in three seasons with L.A.

Who literally had nowhere important to go.

Who said to me, “I literally have nowhere important to go.”

Why the ol’ wrap it up? Because somewhere along the way, on the path from Iverson and Garnett to LeBron and Steph, the NBA came to the realization that we, the sports writers, need the NBA far more than the NBA needs us. The chilling part of that idea? The NBA is correct. Whereas four decades (and some change) back the league was televising the finals on tape delay, it’s now an entity that generates $10 billion annually. Players and agents rule the roost. Twitter and Instagram feeds have eliminated the importance of its antiquated (aka: us) messengers. All major sports leagues (and teams) boast their own in-house media staffs that primarily write positive fluff about the entities (See: Rosenthal, Ken for what happens when someone dares violate the code). So why should Goliaths like the NBA give newspaper writers power when half the time they’re going to rip a player or coach (to dwindling readerships)? What’s the gain?

Hell, look at the New York Knicks, a cesspool of an organization with a ruthless owner and a startling track record of diarrhea teams. At some point along the line, the Knicks decided their approach to the press could be stated in two words:

Fuck.

Off.

Soooo … you’re an ESPN reporter who wants to snag 20 minutes alone with Julius Randle? Nope. Work for The Athletic and aspire to dive deep into the mind of Miles McBride? Hahahaha. You’ll take what the Knicks offer (maybe an obstructed seat to watch the game) and deal with it. Have a complaint? Take it to Derek Lapinski. He will feed it to the nearest goat.

The negatives (for the Knicks) to such media hostilities: None. New York generates the second-highest revenue in the league. Bling. Bling.

The problem is that the Knicks are not alone, and the NBA is not alone. Pre-Covid, across-the-board media access was in decline. Mid-Covid, it has largely come to a halt. This, of course, is understandable. More than 800,000 Americans have died. Thanks to the Delta and Omicron variants, Covid has taken the handoff from Marc Wilson, found a hole and burst down the sideline and through the Kingdome tunnel. There are more important issues than the plight of lowly sports journalists, and I have yet to hear a peer complain about locker rooms and clubhouses being unfairly closed during the pandemic. “I’m not sure what else leagues were supposed to do,” said Ryan S. Clark, who covers the Seattle Kraken for The Athletic. “You can argue it’s hurt coverage, but there are more important issues. Like health.”

“I get why access has changed during a worldwide pandemic,” said Andrew John, a sports reporter for the Desert Sun. “But my worry is that the kind of access we had been used to has changed for good.”

And that is the thing.

The thing.

The thing.

The thing.

The thing that has me worried.

The thing that has you worried.

The thing that has (I believe) the vast majority of sports writers worried.

That this is the end of access as we know it.

That our landscape is forever changed.

I communicated with about 25 media members for this week’s piece.

I communicated with Frank Bonner II of the Daily Memphian and Sean Keeler of the Denver Post. I communicated with C. Trent Rosecrans, Lindsay Jones and Jon Krawczynski of The Athletic and Hunter Shelton of the University of Kentucky student newspaper. I communicated with journalists who would only talk off the record (you know it’s serious when journalists refuse to attach a name) and journalists who pointed me toward other journalists.

And with the exception of Shelton (a legit talent, but a bit too green to fully grasp the historical awfulness of where we sit), the belief was this: We are never fully going back, and our collective futures involve limited access and a whole lot of Zoom.

“Anyone who thinks the open locker room will one day return is a foolish optimist,” said one veteran NFL scribe. “I hope it does. I know every writer who covers the NFL hopes it does. But when in the world has something that’s been taken away then been graciously returned? Especially when it comes to the media and access.”

Rosecrans, the excellent Cincinnati Reds beat writer, said he’s heard of Major League Baseball union members raving about the benefits of a far emptier clubhouse. “They think it’s great without any of us in there,” Rosecrans said. “A lot easier.” Jones, the Athletic NFL chronicler and president of the Professional Football Writers of America, wonders whether the old landscape will even be recognizable. “By the time this is all over you’re going to have multiple years of players who never had open locker rooms,” she said. “My big fear is the longer it’s gone, the more likely it stays gone. It’s a real concern.”

One of the biggest obstacles is oomph. Or, in the case of the sports media, lack thereof. Although most major sports have writer associations that try and stand up for scribes, they’re more George McFly, less Biff Tannen. The Pro Basketball Writers Association, for example, can insist locker room access return when Covid fades. Hell, it can demand its return in a strongly-worded letter to Adam Silver. But when the NBA (Or NFL. Or NHL. Or MLB.) says no …

“We journalists tend to have far less power than people might think,” said Jones.

If you’re reading this, and you’re not a reporter, maybe it all sounds like babyish nonsense. Wha, wha—I can’t awkwardly ask Yu Darvish and Josh Giddey questions as they strip down into a towel. Wha, wha. Which, from afar, makes sense. But the thing about covering teams—about really covering teams—is it comes down to access. To building trust. To shooting the shit. It’s about finding two or three or four or five go-to sources who can tell you what’s up and what’s down; what’s left and what’s right. Those are the ways great stories turn into great stories. You bust your ass fighting to establish connections, and then—when needed—those connections hook you up. As a baseball writer (and even as an author) I have a handful of go-to peeps. We all do.

But now, under Covid guidelines, that’s dead. In the four major sports, the vast majority of post-game interviews are via Zoom (or, in some cases, miniature live press conferences). The team PR staff picks out the two or three players who will appear, and all journalists share that material. Cultivating sources—goodbye. Angling to ask a solo question after the crowd of rivals disperses—goodbye, too. Original reporting—(largely) goodbye. “We make the meal with their hand-picked ingredients,” said Stroud. “One week we were only given special teams players. Like it was a damn theme week.”

Said Alan Shipnuck, the veteran golf writer: “It sucks. Totally sucks. Every other sport is contained within a stadium, and all those sports have very clear places for players to move from A to B to C. A golf course is 150 acres, so you could always get guys during a practice round, walk with them and talk. Well, no more. That’s been taken away. You can’t get inside the ropes anymore. The putting green, the parking lot—all the spots you could get guys have vanished. We used to have open locker rooms. We’ll never get that back. And the coverage will really suffer.”

It already has.

Pick a newspaper—any newspaper. Or Sports Illustrated, ESPN, The Athletic, The Ringer. Good writers still write beautifully. A tight game remains a tight game. Storytelling is storytelling. But the riveting in-depth features that so many of us live for … well, they’re just not there. At least not as they once were. You can’t smell a new baseball via Zoom. You can’t feel raw emotions via Zoom, either. People don’t cry on Zoom as they do in person. Don’t laugh as much, either. Just as a 25-minute chat with Grandma Norma via Zoom isn’t the same as being in her kitchen, a 25-minute chat with Myisha Hines-Allen via Zoom is flat and limited. “The all-around quality has slipped,” said Shipnuck. “The intimacy is gone.”

“I’m not sure how much readers notice,” said Jones, “but those of us inside football media know the coverage has been worse. I hear people from the league say, ‘The coverage is great! You’re not hurting for access!’ But, no. They’re wrong. The depth of coverage you get from being in a locker room is missing. And the number of voices are missing. Hearing from the same two or three guys every week is boring.

“For everyone.”

You’re feeling helpless.

I get it. Because I’m feeling helpless, too.

But then I made two final calls, and my faith was a bit restored. Not totally restored. But a bit. A flicker of hope. First, I reached out to Rob Butcher, longtime vice president of media relations for the Cincinnati Reds. Second, I reached out to Jason Zillo, longtime vice president of media relations for the New York Yankees.

I’ve worked with both men before, and they’re among the best of the best. Devoted to their teams while also respecting and understanding the needs of the sporting press. Honest, trustworthy, straight-shooters. I certainly can’t say that about every PR person I’ve engaged with. But Rob and Jason—top shelf.

So I called Rob, and I told him my concerns. We spoke for about 40 minutes, and what I heard him utter both surprised and pleased me. “Honestly, Jeff,” he said, “I don’t think the majority of players care whether the clubhouse is open or not. We have a really good group of media here, we usually have really good guys in the clubhouse, our manager [the delightful David Bell] very much understands the media. I’m not gonna say none of the players enjoyed having an emptier clubhouse. But I don’t think if you polled the players a high majority would vote to keep it closed.”

Rob went on to say that media matters. That reporting matters. That he sees the proof in what he reads, and that access makes a difference in the depth of work concerning the Reds. “I like seeing stories with multiple voices,” Butcher said. “Nowadays, with the way things are, when your team is at home you can’t go to the other side and talk to five players. That’s a loss.”

Zillo proudly calls himself “a media guy”—and wears the tag as a badge of honor. He grew up in Youngstown, Ohio reading about his beloved Steelers. He knows what it is to have ink on your hand, to fold over a front page. “Ever since I’ve been with the Yankees there’s been a really strong tie between the team and the press,” Zillo said. “It goes back to David Cone and Chili Davis, was passed on to Jeter and Bernie, and now to this generation. This organization embraces the media. Really, we do. I certainly don’t wanna be the PR guy who ruins that.”

Zillo said his job during Covid is somewhat simpler than in the past. He doesn’t have to be in nine places at once. “There’s no photo shoot at 2:30, a meeting with the GM at 3, the manager meeting the press at 3:15,” he said. “So, yeah, it’s easier to maintain. But I don’t like it as much. I miss the buzz of the locker room and the writers. I really do. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I’m 100-percent pro-media.

“I want it back to the old days.”

The Quaz Five with … Doug Russell

Doug Russell, a veteran sports reporter and anchor, hosts the “The Game Night” on 97.3 The Game in Milwaukee as well as “The Doug Russell Podcast.” He’s known as one of the best peeps in media—which is impressive, because this industry (rep be damned) is overflowing with gems. One can follow Doug on Twitter here.

1. With Covid ending many commutes and podcasts surging, is there still a bright future for sports talk radio? Or has the medium had to adjust to changing times/demographics?: Absolutely, and yes. I think there will always be a market for original content, but that doesn’t mean the same show you hear today will be the same show you hear five, 10, 20 years down the road. We know that podcasts are here to stay, but radio should not run from the medium; rather radio should embrace it. Terrestrial hosts should have either an “in case you missed it” type of podcast available or a separate podcast to have in-depth, unfiltered, uncensored conversations a radio clock (and the FCC) won’t allow. Ideally a host would have a podcast that can accomplish both. After all, just as podcasts are here to stay, so are podcast ads (BetterHelp, ZipRecruiter, HelloFresh and others spend most of their ad dollars in on-demand audio for a reason).

That said, the advantage that radio (terrestrial or satellite) has is its immediacy. And in an era of an audience craving instant news and analysis, no podcast will ever be able replicate that connection (in an audio-only format) that is radio. Late-breaking injury news for fantasy players you won’t hear on a podcast, for example. Postgame shows that fans can react to what they just saw/heard won’t be on podcasts. And even today, your favorite host taking your call or reading your text live on the air still has cache. Radio shows just have to be unique … and mostly local. There aren’t very many national shows that cut through the noise anymore because fans generally only care about their own favorite teams. The best national shows know this and pivot well to broad topics rather than Xs and Os talk, but most network shows are just inexpensive filler nowadays. Sports radio most certainly has a future. But programmers and hosts have to know how to adjust as the times do.

2. You posted 10 very sane rules to Twitter. And they're beyond lovely. But how, in this cesspool of hell, have you been able to maintain them?: Sports radio is supposed to be fun. It is supposed to be an escape from real issues of the day. The “candy store of life” someone described sports to me once. Twitter, as an extension of our respective brands, becomes an extension of our shows when we aren’t on the air. I used to be the worst (well, one of the worst) at clapping back on Twitter to trolls. But trolls live off that negativity. The thing that drives them the craziest is being ignored. Once I realized that, I gained a lot of control (and time) back. After the last couple of election cycles, I also learned that you aren’t going to change someone’s mind about something they don’t want to change their mind about. Pushing someone—particularly a stranger—to seeing an issue your way only pushes them back further toward the echo chamber they came from, so why waste my time, and get only the aggravation in return? I will not debate politics on Twitter because no one follows me for my political views. My brand isn’t built on that. A smart programmer once cautioned me to “stray from sports if you have to, but you do it at your own peril.” I don’t look down on anyone who does want to mix sports and politics. It’s just not my jam anymore. Again … what I said about the echo chamber. At the end of the day, I’m not going to change anyone’s mind about who to vote for with a tweet. But I also won’t be sworn at. That’s just a respect thing from my upbringing. I would not allow someone to insult me in my own home, so why would I allow it on my Twitter feed? Social media gives everyone a platform to spew whatever their beliefs are, and a lot of people’s beliefs are pretty ugly. So, I hit a breaking point. I don’t know that it goes a whole lot deeper than that. That’s where the rules came from, and so far, they’re working beautifully.

3. What's the strangest moment of your career?: What a great question. Very early in my career I was reporting on the EAA Fly-In in Oshkosh, Wis. It’s a huge air show where homemade planes fly in for exhibition and competition; in the aviation community it’s a pretty big deal. Anyway, every afternoon there is an air show featuring small planes and their acrobatic skills. We had a command center trailer in the media center parking lot with our host running point on our coverage – and as the local station in town, we broadcast the entire event live. We had the PA mic piped in, the host in the command center, and two reporters on each end of the flight-line on wireless mics providing color. This particular year, I was assigned the south end of the runway with another reporter on the north end. That’s when, um, nature called. I radioed ahead to the command center and to the reporter on the north end to not toss it to me for our next scheduled hit because I would be indisposed. Of course, the reporter on the north end didn’t hear me and tosses it right to me on the south end. What can you do, right? I had the schedule of the next planes up with me … I knew what they looked like from earlier in the week. So, whilst on the Port-a-John eliminating my lunch, I was live. On the air. Describing what I could not possibly see. Despite the situation I found myself in, it was not the shittiest live report I ever did (rimshot).

4. What, in your opinion, is the difference between someone who lasts in the medium (sports radio/TV) and a flash in the pan who comes and goes?: Passion, probably. Talent helps, but there are talented people who get fed up with the terrible hours, terrible bosses, and terrible pay at the start of their careers and leave. No one who has done this for any length of time has had it easy. Even Dan Patrick, who I think is one of the best to ever do this, talks about how he had to reinvent himself after he left ESPN with almost no distribution (or even studio) for his new show. I’ve had to take part-time radio jobs after another gig ended just to get back in the door at a different place. But I know who I am, and I know that every setback is a temporary one. I also know that no one who has ever worked with me would say that I had a bad work ethic or was lazy. That has always been my in. Over the years, I have had wonderfully talented co-workers quit because of lousy leadership. During an HR inquiry to a particularly challenging program director I once had, the company investigator asked me why I just didn’t quit? All I could tell her is “this too shall pass.” And it did. I outlasted my boss and life moved on, despite having to endure the daily lack of respect this individual provided his staff. I got stronger for it; others didn’t. Flashes in the pan cannot handle setbacks. This is a most humbling business. If you cannot roll with the punches, you aren’t going to last long.

5. Rank in order (favorite to least): pumpkin-scented candles, Ron Dayne, playing catch with a friend, Tammy Baldwin, Ray Bans, Cecil Cooper, "Raiders of the Lost Ark," Lake Geneva: Hmm. Okay. I’ll preface this by saying I’ll always prioritize people over inanimate objects. I’ll also say that there is nothing on this list I find particularly objectionable, so even my last place entrant is a net-positive for me. And politicians generally do not curry much favor with me as a whole because I view a politician like a diaper: they should be changed often and for the same reason. That said, the politician you name has even her staunchest critics disarmed by her personal warmth and charm; insomuch as they might disagree with her political stances. So, with that disclaimer in the rearview mirror: Playing catch with a friend (easy No. 1), Ron Dayne, Cecil Cooper, Tammy Baldwin, Ray Bans, Lake Geneva, “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” pumpkin-scented candles

This week’s college writer you should follow on Twitter …

Jake Dye, senior at the University of Alaska Anchorage and executive editor of The Northern Light.

One of the things I love about this part of the ol’ Substack is stumbling upon writers and articles I normally wouldn’t see. And this morning I somehow found myself reading Jake’s review of “Unpacking” and falling in absolute love with this perfect lede …

It’s a reminder that sometimes less is more; that you don’t have to unroll 500 words to deftly break down a point. I went on to go through Jake’s catalogue of work, and the excellence sparkles all around. This is a young man who knows his shit, knows how to write and combines smarts with precision into routinely great work.

Jake is on Twitter here. Bravo, kid …

Yet another story of one of my myriad career fuckups …

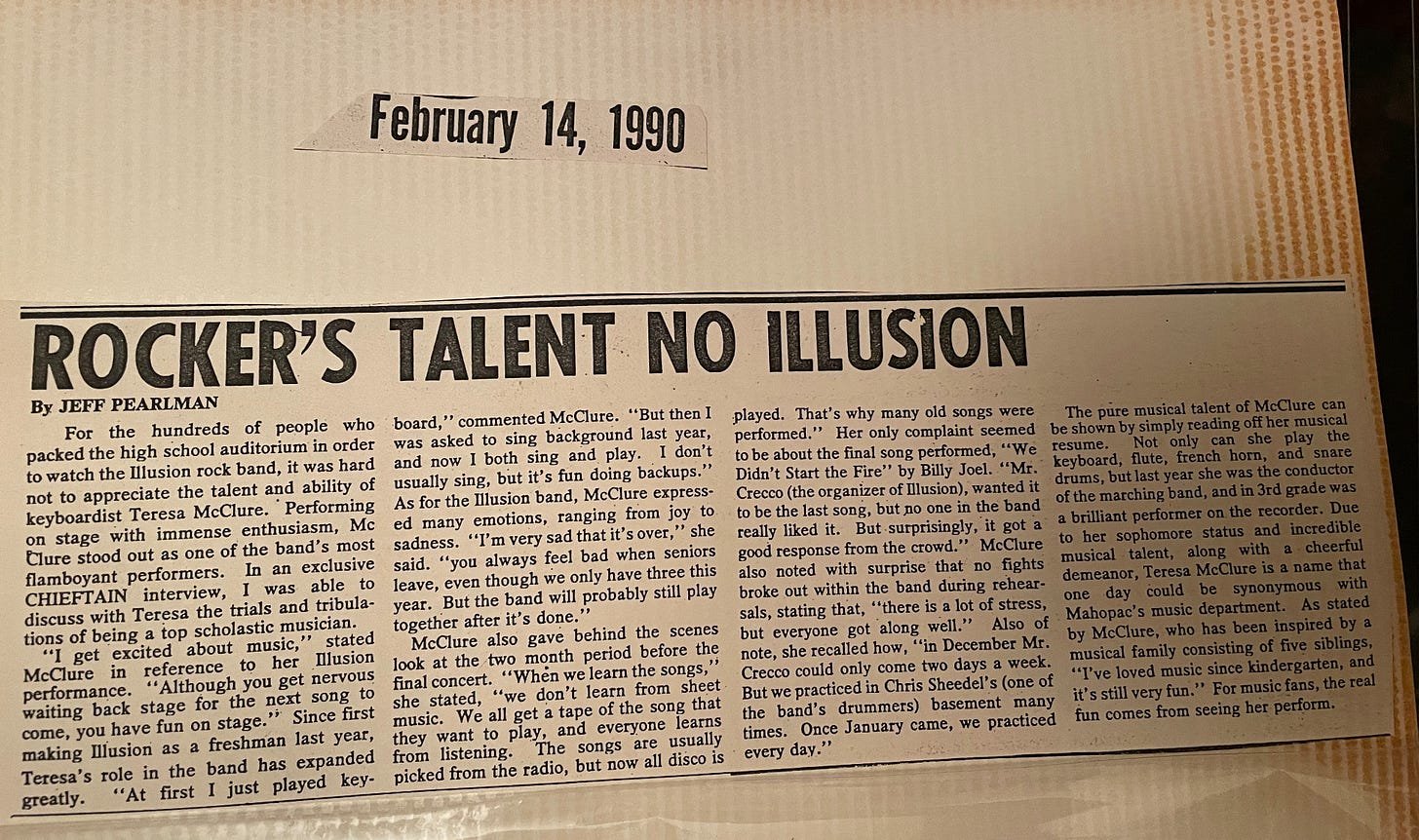

I was a senior at Mahopac High. Sports editor of The Chieftain.

Our school had a rock band, Illusion, which held an annual concert that was wildly popular. I went. The keyboardist caught my fancy. I found out her name was Teresa—Teresa McClure.

I came up with a plan. I would meet her, write a story about her for the paper. She would fall madly in love with me because … charm.

Everything went perfectly. We met in the library. Chatted about music and Illusion and dreams. The story not only ran, but landed atop the front page. On Valentines Day! This was fate.

I devised a follow-up plan. I would call her, lie to her. So I did—I called, asked to speak to Teresa.

“Um … hi, um, Teresa? This is Jeff Pearlman. I wrote the article about you.”

“Oh. Hi, eh, Jeff.”

“So, um, eh, um, my dad always gives me $20 whenever I get a front-page article. And, um, I wanted to see if you’d wanna go out some time. With, eh, me.”

“Sure,” she said.

I was giddy.

Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy. Giddy.

Teresa proceeded to avoid me the rest of the year. We never went out.

The power of the pen only goes so far.4

Random journalism musings for the week …

Musing 1: Woke up this morning to an ESPN.com interactive experience, INSIDE THE 2001 MIAMI LOCKER ROOM. And it’s brilliant—absolutely brilliant. But also started me down the road of googling the various players to learn what their lives became post-football. Take my word: If you don’t wanna be particularly depressed, avoid the exercise at all costs.

Musing 2: Really strong work here from the Associated Press’ Michael Biesecker on, ASHLI BABBITT A MARTYR? HER PAST TELLS A MORE COMPLEX STORY. I’m a fan whenever journalists take the time to probe, dig, explore—and not let partisan actors (of any stripe) define and dictate a narrative.

Musing 3: I remain inspired and dazzled by the ways we can now tell stories—and get them out to so many people.

Exhibit A …

Musing 4: Here’s the perfect example of deliberately misleading headline writing at work. Breitbart publishes a story headlined, 2021: BORDER PATROL AGENTS FACED HISTORIC LEVEL OF LINE-OF-DUTY DEATHS. Which, of course, implies that the border is super dangerous and there’s lots of murder and Biden has fucked it all up and … and … and …

Um.

Of those 15 deaths, 13 were Covid-related. Thirteen.

Which changes the entire meaning of the article.

Musing 5: You’re Yaron Steinbach. At some point in life you thought, “I wanna be a journalist! I wanna write important stories that serve humanity! I wanna make a difference!” Fast forward. It’s 2022. You work for the New York Post. And your piece has gone viral. The headline: 90 DAY FIANCE’ STAR RETIRED FROM SELLING FARTS AFTER HEART ATTACK SCARE.

Musing 6: So Kelly Ernby, a deputy district attorney out here in Southern Caifornia, died Monday from Covid And I find the Orange County register’s headline (KELLY ERNBY, DEPUTY DA AND FORMER ASSEMBLY CANDIDATE, HAS DIED OF COVID COMPLICATIONS) inexplicably … weak. Why? Because it turns out Ernby was unvaccinated, and during a recent Assembly campaign spoke forcefully of her Covid skepticism. Considering she died (literally) of Covid, that information has to has to has to be in the headline—politics be damned.

Musing 7: Ken Rosenthal is one of the absolute gems of sports media, and his curb kicking by MLB Network following nearly 12 years is a neon reminder that working for a team/league is not—and can never be—independent journalism. According to multiple reports, the network ditched Ken because of criticism of Rob Manfred, MLB’s shitty commissioner.

Musing 8: In case you need one, here’s your weekly reminder that Jason Whitlock used to matter, stopped mattering, realized he stopped mattering, joined the dark side and now lives a sad, pathetic, lonely life as a floppy douche.

Musing 9: Some legitimately fantastic storytelling from Jay R. Jordan of Chron in a piece headlined, BODYCAM VIDEO SHOWS HOUSTON COP SPEEDING, DRIVING WITH 1 HAND BEFORE HITING AND KILLING PEDESTRIAN WITH PATROL CAR. It’s super easy to overwrite such stories. Jordan just let the material tell itself. Bravo.

Musing 10: Ah, nothing to see here on the Today Show this morning—just a batshit crazy (and weirdly sympathetic) interview with Jenna Ryan, the wealthy white woman who invaded the U.S. Capitol. To quote a friend of mine: “They let her say how her business has been hurt yet she still believes she has the right to believe what she does or something. They were not hard hitting questions but I was seething so don't remember. The whole fact she was on was sympathetic, no news value, just ‘Here's a pretty blonde who could be your neighbor and, oh yeah, tried to overthrow the fucking government.’

I 100-percent agree.

Musing 11: New Two Writers Slinging Yang stars Chris Long, former NFL defensive lineman, with a fantastic chat about athlete perceptions of the media. Link here.

Quote of the week …

“If someone says it’s raining and another one says it’s dry, it’s not your job to quote them both. Your job is to look out and find out which is true.”

One never knows with Jerry Jones walking the planet.

Kevin.

At the time.

Nice aftermath. Years ago I did a piece about all the girls I’d wanted to date as a youngin’, but never did. I reached out to Teresa. Our families went apple picking. We’ve remained Facebook friends. She’s nothing short of delightful. And—judging by her husband, her kids and her long-ago decision not to date the loser writer—a strong judge of character.