The Yang Slinger: Vol. XXVIII

Monday Night's terrifying hit that left Bills safety Damar Hamlin fighting for his life wasn't merely a nod to human fragility. It was a reminder how hard covering a tragedy can be.

With 5 minutes and 58 seconds remaining in the first quarter of last Monday night’s football game between the Bills and Bengals at Cincinnati’s Paycor Stadium, Matt Parrino gazed downward toward his laptop. This is what much of life in the press box is like for the @syracusedotcom Bills beat writer. Watch a play unfold. Type. Watch the next play unfold. Type. Watch the play after that unfold. Type.

It’s the 2023 vision of beat writing—one’s primary task isn’t the following day’s newspaper1 or even a story for the website. No, it’s keeping readers abreast of the action as it transpires.

So that’s why Matt was looking at his screen in the seconds after Damar Hamlin, the Bills’ second-year safety, collided with Bengals receiver Tee Higgins, then fell to the ground. “I saw the hit, thought nothing of it, started to type,” Parrino told me Thursday afternoon. “I had binoculars with me, and after typing I looked down at the field. One of the first things I saw was an EMT grabbing a walkie talkie and screaming into it. There was a fear in her face, telling me this wasn’t a normal injury. That this was different.”

Parrino, the excellent fifth-year Bills chronicler, thought he’d seen much in his time as a journalist. Unexpected comebacks. Breathtaking throws. Highs. Lows. Accomplishments. Failures.

What was to follow, however, would take him to unchartered turf.

•••

If you do this sports journalism thing long enough, you’ll cover tragedy. Even though athletes are treated as Justice League-level superior beings, created from Tungsten and Krypton’s inner core, they are (in fact) made of the same shit we are. Namely, flesh and bone and snot and water. Once, while covering the Major Leagues for Sports Illustrated, a butt-naked Marlins third baseman named Wes Helms deliberately farted in my face. I experienced the whole thing, and can assure you it was the tushy and gas of a homo sapien.

So … hype be damned, these people we’re covering are human. And humans suffer. My first taste of this came way back on April 22, 1988 (my 16th birthday), when my tiny hometown of Mahopac, N.Y. was overcome by grief upon learning of the passing of a local football star named Bryan Higgins. Although I didn’t know Bryan personally, he had been one of Mahopac High’s all-time great standouts, and was a sophomore strong safety for Division II SUNY Albany when—as part of a fraternity stunt gone wrong—he waded into an electrically charged pond and died. I remember catching wind of the tragedy and finding myself … bewildered. This can’t be. This can’t possibly be. Bryan Higgins is 20. A football stud. A guy breaking tackles and throwing blocks. Dead? No way. Bryan Higgins isn’t fucking dead.

Only, he was.

Fourteen years later, I was covering baseball for Sports Illustrated, doing the Spring Training slog through Arizona, when news broke that Mike Darr, 25-year-old San Diego outfielder, died after the SUV he was driving (while drunk) rolled near the team’s headquarters in Peoria. I was dispatched to Padres camp, and still remember the zombie-like state of the team’s players, coaches and administrators. Mike Darr had been a strapping 6-foot-3, 205-pound athletic specimen, one whose Popeye-esque arms were coated in colorful tattoos. He was brash and bold and ready to take on all comers. Like Higgins’ death, this one simply didn’t compute. How could Mike Darr no longer exist?

But here’s the thing. The really tricky thing. The Padres were allowed to mourn. Hell, they were expected to mourn. It was part of the grieving process—so clergy were brought to camp, therapists were made available, time away was granted. We journalists, however, are afforded no such luxuries. Even though we feel the same shock, suffer the same nightmares, endure similar emotions—we are immediately thrust into action. Instead of seeking solace, we ask questions. Then more questions. Then more questions. And while we like to think that, somehow, our presences help in the healing process, well … that’s sort of debatable.

Back in the spring of 1993, for example, the sporting world (really, the country) was rocked when three Cleveland Indians pitchers—Steve Olin, Tim Crews and Bobby Ojeda—were involved in a boating accident on Little Lake Nellie in Clermont, Florida. The team was enjoying a rare off day, and the three players used the time to go out on the water. Crews, a veteran right-hander who was piloting the boat, had a blood alcohol level of 0.14, and he somehow slammed the vessel into a long pier, killing himself and Olin while nearly beheading Ojeda.

At the time, Paul Hoynes was in his 11th season covering the Tribe. Shortly after the accident happened, he was inside his rented apartment, watching ESPN with his father, Jim Hoynes, and uncle Dever Hoynes. “A lot of the players were staying in the same place where I was, so I went down there and a bunch of them were gathered around, but no one was saying anything,” Hoynes recalled. “I gradually started to find things out, but not a lot. No one wanted to talk.”

Hoynes decided to drive out to Little Lake Nellie, and was shocked by the scene: A body of water the size of a pimple. A battered boat pulled up toward the shore. Thick seaweed coating the surface, with a crude incision where the boat had knifed through. “After that I went to the hospital where Crews was taken, but nobody had anything to say,” Hoynes said. “So I wrote for a little bit, then decided I’d knock on some doors.”

And this, truly, is the hell of covering tragedy. Because Paul Hoynes, all-time great baseball writer and an unambiguously good guy, didn’t merely knock on any doors. No. He approached the door where Steve and Patti Olin were living with their three young children. He knew Patti was surely going through the depths of hell—she was 26 years old and newly widowed. But, eh … um … this job.

This fucking job.

“I was sitting there in front of the door,” he recalled. “Do I knock? Do I not knock? Do I knock? Do I not knock?”

Hoynes knocked.

And.

Waited.

For.

Someone.

To.

Open.

“It was terrible,” he recalled. “Someone with Patti came to the door and told me she didn’t want to talk. That was fine with me. I’m sure I was relieved. Mike Hargrove was the manager of the team, and when he saw me he wasn’t pleased. I couldn’t blame him. But I had a job to do.”

And while those who don’t work in journalism may well consider Hoynes knocking on Patti Olin’s door to be a satanic endeavor, it was something that needed to be done. And, really, that’s probably the biggest part of covering tragedy in the sporting universe: You will do things that absolutely, positively suck. You will knock on doors knowing the people behind said doors won’t want to talk. You will ask questions as people sob and scream and wallow. You will request that folks break down their feelings at the precise moments they are experiencing nothing but despair.

It’s the worst of the worst of the worst.

But, when done correctly, it can result in journalistic gold.

And help people heal.

The First Rule

The first rule of tragedy coverage is also the first rule of journalism: Get your shit correct, and overload on details.

I know, I know—basic stuff. But it can’t be overemphasized when it comes to tragedy. You absolutely, positively cannot have incorrect and/or missing information. Hoynes, a veteran even back in 1993, learned this the hard way. In one Plain Dealer article, he inadvertently botched the placement of the three players on the boat. “I had them sitting in the wrong order,” he said. “And maybe you think, ‘Eh, not a big deal.’ But emotions are high and everyone is suffering, and the readers are relying on you for information.” Looking back, Hoynes said he missed a press conference where law enforcement officials broke down the boat seating arrangement—”and that was really dumb on my part. I should have been there.”

Fifteen years after the Indians nightmare, Jaquan Waller, a prep running back at Greenville-Rose High in North Carolina, died from head injuries suffered in a game. Tony Castleberry was a young scribe for the Daily Reflector, and he went all in on the emotions of teen loss. He spoke with family members. He attended Waller’s funeral. He paid close attention to tears, to hugs, to sobs. “[But] I wish I had taken a deeper dive into the medical side of Jaquan's situation instead of (perhaps understandably) focusing on the emotional component,” Castleberry DMed me. “Talking to more doctors/head trauma specialists/athletic trainers in the beginning would have provided me (and readers) a broader, more informed perspective. The emotional component was always gonna be there. This kid was a great player and beloved in the community. I probably could have done a better job explaining exactly how he died as opposed to covering the reaction.”

Back a decade ago, while working on my Walter Payton book, I reached out to Rick Kane, a former Detroit Lions running back who had played against Sweetness and surely had plenty of stories to tell … had he not died earlier that year. His widow (rightly) tore me to pieces, asking how could I possibly not know Kane was gone. I felt about two inches tall, and have never forgotten the awfulness.

So, yeah. Get your shit right.

The Second Rule

The second rule is sometimes a bit hard to get our heads around, but it’s unambiguously true: Sports don’t matter.

Say it aloud: Sports don’t matter.

I spoke with Parrino three days after Hamlin’s injury, and he had yet to write a single word about Josh Allen’s throwing arm or Stefon Diggs’ conditioning. There was no talk about how the accident impacted the Bills’ Super Bowl hopes, and certainly nothing about whether anyone could step up to fill in at safety. “I haven’t done anything at all about the games—part because I’m struggling, part because it feels so meaningless,” he said. “Are we really talking about a game when someone’s lying in the hospital, fighting?”

The answer, of course, is no—we’re not. When the Indians’ pitchers died, Hoynes went nearly a week without chronicling fastballs and sliders. Lesley Visser was the New England Patriots’ beat writer in 1978 when wide receiver Darryl Stingley was paralyzed in a pre-season game against the Raiders. “What I learned at the Globe from the greatest beat writers and columnists,” Visser told me, “was to notice details and have them in my head on deadline.” What she also learned (on the fly) was that when a player’s back is broken, the quarterback battle between Matt Cavanaugh and Tom Owen is meaningless.

On the night of Bills-Bengals, the always-available-to-be-a-dick Skip Bayless thought it wise to Tweet this to his 3.2 million followers …

The backlash was hostile. Not because the question was, technically, unreasonable (I mean, I’m sure some people were wondering how the schedule might be impacted), but because it ignored the raw human suffering at hand in order to focus on … football.

“I think we saw with the reaction to Skip Bayless ... the game(s) don't matter,” said Jared Aarons, a morning anchor and reporter for San Diego’s ABC 10 News. “But at some point they will. Sport has always been a great distraction, but it's also a great way for a community to come together and heal. When the games resume, it's part of people's grieving process. Getting back to some semblance of normal will help a lot of them. But this won't be a normal game at all. Many of them won't even give themselves time to grieve or process until after that first game when all the emotions will flood out. Be prepared for that moment and be cognizant of it. Some of the players/family will want to celebrate a win. Let them. Some of them will be bawling because there's a finality in that moment they hadn't dealt with yet. Let them.”

The Third Rule

The third rule is fairly basic, but one often ignored by inexperienced chroniclers of suffering: Always (and I mean always) go to the hospital.

In the aftermath of 98 percent of sports tragedies, the hospital is the hub of operations. You have the injured athlete at the hospital. You have the family members of the injured athlete at the hospital. You have the friends of the injured athlete at the hospital. You have the doctors, the nurses, the fans holding vigils. Absolutely everything you want/need as a reporter is located at the hospital.

And while you may well have to tiptoe past a NO SOLICITORS sign, then casually (nonchalantly) stroll through a hallway that could be, cough, off limits, it’s the must of must of musts.

For Parrino, the University of Cincinnati Medical Center (where Hamlin is being treated) has meant everything. Two days ago, while standing across the street from the facility, Parrino and a large handful of media peers spotted Dorrian Glenn, Hamlin’s uncle. “I’m not sure who first saw him, but about eight or nine of us interviewed him on the sidewalk,” Parrino recalled. “Usually when you’re with a bunch of other reporters you feel competitive, but there was none of that. I felt like the more people there to share and spread the news, the better. As a collective media, we needed to get it out there, because so many people cared.”

The Fourth Rule

The Fourth Rule should probably be the First Rule. But I already have a First Rule, so it’s Fourth with a gold star: Be empathetic. “The truth is undefeated,” said Jimmie Tramel, who covered the Oklahoma State men’s basketball team for the Tulsa World in 2001, when 10 people died in a plane crash. “Know what else is undefeated? The golden rule. In pursuit of the truth, treat people the way you want to be treated. That’s especially true when dealing with people impacted by tragedy.”

In many ways, that’s the No. 1 problem with Skip’s Tweet—it’s zero percent empathetic, 100 percent asshole. And when folks are at their lowest, they deserve your empathy. So that means, even as a reporter, it’s OK to tell a grieving relative how sorry you are. It’s OK to cry during an interview. It’s OK to ask for a tissue. It’s OK, if you’ve suffered a similar loss, to show your understanding. In 2015 Chris Murphy was a preps writer for the Forum of Fargo-Moorhead when Connor and Zach Kvalvog— local basketball-playing brothers—died in a car accident en route to a hoops camp. “That turned really sad, “Murphy said. “This was their only children, and the parents slept in the funeral home the day before the funeral.”

Murphy recalls shaking when he made phone calls, and shaking even more when he knocked on doors. “I made sure that family and friends knew they didn't owe me anything,” he said. “If they want to talk, I'm here. My big thing if I got them to talk was, ‘I want to know about (the name of the dead).’ Not, ‘So what does this feel like?’ or ‘Where were you when they died?’ Never open with that. That's grief porn. You're trying to write about a life, save the death questions for later. Empathy and respect. You don't want to write these stories, but the dead deserve them to be told.”

The Fifth Rule

The Fifth Rule can be used all over the journalism landscape, but it certainly applies to tragedies: Seek out the bigger picture.

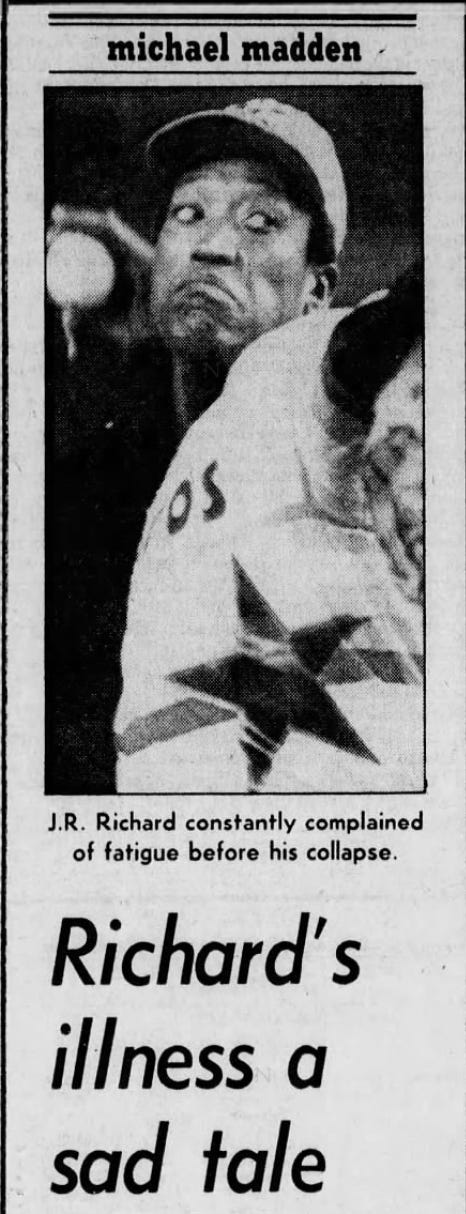

What I mean is, someone dying isn’t merely someone dying. Someone getting hurt isn’t merely someone getting hurt. There are always tentacles that reach out and extend elsewhere. As a top-of-the-head example, when Yankees catcher Thurman Munson died in a 1979 plane crash, it wasn’t just an All-Star ballplayer taking his last breath. It was a midwest kid practicing takeoffs and landings at his hometown Akron–Canton Airport. It’s the story of someone who oozed his place of origin, and maintained the values and ethos of blue-collar Canton. When Darr died in 2002, there were larger stories to be written about, oh, the sense of invincibility so many young athletes carry. Why, just a few days ago CNN.com asked if I’d like to write something about Hamlin. I somehow turned my thoughts toward Chuck Hughes, the former Detroit Lions wide receiver and the only man to ever die in an NFL game (he’s lying on the field in the photo at the top of this entry). While reading a 1971 Detroit Free Press article about his death, I learned Chuck had a one-year-old son at the time who would now be 53. I was wondering what the boy could possibly be thinking, watching Bills-Bengals. So I found Brandon Hughes in San Antonio. We spoke, and he was terrific. The result was this—not the best thing I’ve ever written, but an outside-the-box take.

The Sixth Rule

The Sixth Rule matters because we are—despite what Donald Trump and Co. might believe—human: Take care of yourself.

The weight of tragedy is real, and one thing that happens with journalists is we often either forget to seek help or we self medicate with booze/drugs/whatever. We think of ourselves as observers, when—truth be told—we’re getting hit with the sledgehammer, too.

In 2016, J.C. Carnahan of the Orlando Sentinel wrote some breathtaking pieces on Joe Skinner, a local high school catcher who was battling leukemia with uncommon grace and strength. Skinner was a 17-year-old senior who insisted he would beat the disease and continue with his baseball career at Central Florida. And while the odds were long, Carnahan hoped that maybe, just maybe, the kid could overcome the odds.

When, on April 29, 2016, Skinner died, Carnahan was crestfallen. “I’m not ashamed to say I shed some tears while sitting and writing about him,” he said. “I’ve saved a text message he sent saying how much he loved the story. He died maybe 30 days later.”

Carnahan allowed himself to decompress and examine the pain. As did Hoynes after the Indians accident. As did Visser when the Stingley smoke cleared. As, I expect, Parrino will do as Damar Hamlin continues to make strides and leave the hospital and walk and run and live a full life.

People think we’re impervious to pain.

We’re not.

We bleed ink.

The Quaz Five with … Les Bowen

Les Bowen covered the Philadelphia Eagles for the Philadelphia Daily News and Philadelphia Inquirer from 2002-2020 and spent 38 years as a media member in the City of Brotherly Love. You can follow him on Twitter here.

1. Les, you covered the Philadelphia Eagles for 19 years. What's the weirdest experience from your time on the beat?: The Terrell Owens mess in 2005-2006 was the strangest, I think, though there have been other contenders. T.O. blowing up the team because he didn’t like his contact, mocking McNabb, leaving out part of the apology the team wrote for him to read aloud AND THEN LEAVING THE PRINTED SHEET IN FULL VIEW IN HIS LOCKER ON PURPOSE SO WE WOULD ALL SEE THAT HE DIDN’T READ THE WHOLE THING, telling offensive coordinator Brad Childress not to speak to him unless spoken to, sit-ups in the driveway — really hard to beat that.

2. What's the closest you ever came to thinking a player/coach might slug you?: Never came all that close in the NFL. In hockey, Flyers enforcer Shawn Antoski was upset enough by a Philly Daily News back page headline to jump out of the shower, suds and all, to confront me, but I never thought he was really going to swing. Today we are Facebook friends.

3. My college journalism professor/hero was Bill Fleischman. Selfishly, what can you tell me about Bill?: Bill was a very kind and decent person. By the time I knew him he was mostly an administrator, but I know his work covering the Broad Street Bullies was greatly appreciated. He and his wife survived the loss of a daughter in an auto accident, and carried on with dignity and grace. I’m not sure I could have done that.

4. I always felt Donovan McNabb could have been an all-time great, but is merely an all-time good. Am I right? Wrong? Somewhere in between?: You are exactly right. He had enormous talent, and I stood up for him a lot in the early parts of his career because so much of the criticism was nakedly racist. You’ll recall the Rush Limbaugh ESPN business. But Donovan never matured all that much, as a person or as a player. He remained kind of a good-natured goofball. Like some other athletes I’ve known, he trusted his own physical superiority. When his body started to break down, I think he lost something in terms of confidence and purpose. He felt betrayed when Andy Reid traded him. He was pretty much the only person in the world who didn’t see that coming. Donovan needed a couple more really good seasons then to become a true Hall of Famer, but I thought he more or less went through the motions with Washington and Minnesota. His identity was tied up in being quarterback of the Andy Reid Eagles. I think he thought he would do that for as long as he wanted.

5. Why'd you leave newspaper? Do you miss it?: Several things happened. As I was turning 65, Pat McLoone, the Inquirer managing editor for sports I had worked with and for since we were Daily News copy editors in the mid-‘80s, was replaced by a new sports editor, someone I didn’t know. I would have trusted Pat with my life. I’m sure the new editor is a fine person, but his mandate was to shake things up, bring in a younger, more diverse staff, and I couldn’t see a lot of future in that for me. The paper offered the best buyout terms it had offered in 20 years. Part of that was extended medical insurance that took me to where I could go straight into Medicare. Then there was my mom down in Charlotte. She was getting toward the end and I wanted to spend a lot more time down there — which I did. It was tough, though, because I’m in good health and I still like to write. Plus, this year the Eagles are having a really interesting season, and at times, I’d like to be down there talking to people, in the middle of all of it. I was, for a while, after working out a part time gig with another outlet, but that went away at the end of October. There’s this push-pull thing —- you know you’re going to miss parts of the working life, but the calendar pages keep flipping. My dad put off retirement past 70, dreaded it. Then he retired and he and my mom had some wonderful years, traveling and doting on grandkids. But pretty quickly my dad’s health faltered. He didn’t get as many good years at the end as he would have wanted, partly because he waited so long. Last month, my wife and I visited our elder son in Denver and went on a fairly arduous hike in the Rockies. It was an all-time memory. How many more years will we be able to do that? If I were still covering the Eagles, I would have been in Chicago that weekend, watching them play the Bears. I would’ve liked to have covered that game. But the time with our son and his girlfriend was much more precious. Sorry this answer is so long and rambling. I think for people in their 60s, in good health, who basically like what they do, retirement is a really hard thing. Steve Lopez wrote about this recently for the LA Times. I don’t know that I’ve completely figured it out.

A random old article worth revisiting …

On December 12, 1983, Rex Dockery, the football coach at Memphis State, died in a plane crash. This piece, from The Tennessean’s Larry Taft, is beautifully haunting. I’ve probably read it 50 times over the past few decades. It still gets me.

This week’s college writer you should follow on Twitter …

Andrea Hancock, Northwestern

Andrea is the daughter of Will Hancock, the Oklahoma State basketball SID who passed away in the 2001 men’s basketball team plane crash. She’s the granddaughter of Bill Hancock, executive director of the College Football Playoff.

It’s been around a but, but her piece for the Tulsa World, I NEVER MET MY DAD, BUT I MISS HIM BECAUSE ‘I DO KNOW HIM’ is all sorts of beautiful. This, in particular, is gorgeous writing …

One can follow Andrea on Twitter here. Keep bringing it, kid ...

Random journalism musings for the week …

Musing 1: Mariana Alfaro of the Washington Post’s breaking news team absolutely killed it during (ongoing as of this entry) coverage of the Kevin McCarthy/House of Representatives shit show. The newspaper is obviously loaded with talented scribes, but Alfaro’s doggedness was off the charts.

Musing 2: If you’re a journalism geek (cough, guilty), this week brought forth a Piazza-to-the-Mets-level transaction. Eli Saslow, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post scribe, was signed as an unrestricted free agent by the New York Times. Eli is arguably America’s best long-form newspaper dude, and his work (like this and this) is magic. Enormous loss for the Post, enormous gain for the Times.

Musing 3: Michael J. Lewis, the excellent freelance journalist/blogger, was recently explaining to me why he posts his Wordle scores on Facebook. I’ve never played Wordle. I don’t know how Wordle works. But I’d like to congratulate Mike on this apparently excellent tally …

Musing 4: I was troubled by Stephen A. Smith’s weird apologies on behalf of Dana White, the UFC biggie who was caught on camera slapping his wife. I was equally troubled by Molly Qerim going along for the ride. I don’t have super high expectation for SAS. But it feels like Molly should know better.

Musing 5: I’d never read anything by The Guardian’s Stephen Reicher before (probably because he’s a professor of psychology at the University of St Andrews), but this piece, WITH COVID CASES SOARING AND THE NHS IN TROUBLE, HERE’S HOW TO END THE CULTURE WAR ON FACE MASKS, is excellent.

Musing 6: Randomly, if you’re not following Tom Bear on Instagram, you’re missing out.

Musing 7: A shockingly candid and honest answer from Mike LaFleur, Jets offensive coordinator, on the problems with quarterback Zach Wilson. This is why it always pays to ask your questions. You never, ever, ever know what will come from someone’s mouth.

Musing 8: This week’s Two Writers Slinging Yang podcast stars Mike Organ, longtime Tennessean sports writer and a gem of gems.

Quote of the week …

“We see too little as a failing and too much as a sin. We dismiss those who lack it and despise those who misuse it.”

— Deborah L. Rhode (on ambition)

A paper contraption that used ink to present people with information on a daily, at-home basis.

Jeff,

Excellent, as always. I admire how much care you put into each post. My wife was a reporter at Newsday, part of the team covering the 1993 LIRR shooting. Everyone was hoping Caroline McCarthy might speak to them. she had lost her husband and her son was in serious trouble. Rebecca stayed parked in the hospital waiting room for a few days and in the meantime became friendly with a security guard, because she's a great reporter and also a nice person who would do that anyhow. He came and got her and helped her get Caroline, who really wanted to share her story and needed someone she could trust. Rebeca's empathy won her over, and she became enmeshed in the McCarthy family for the next two years. I am tearing up writing this, because it was such a sad, intense time and also because I am so proud of her. Your post brought me back to that Your rules are right on.